Decoding IPR

Trademark Licensing or Trafficking? Traversing the Legal Maze

Introduction- Decoding Trademark Trafficking

Introduction- Decoding Trademark Trafficking

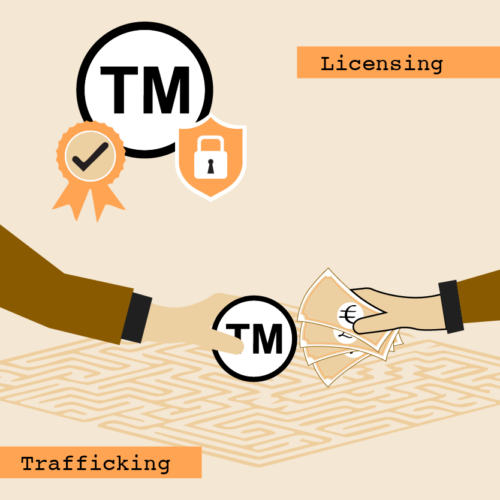

Trademarks serve a crucial role in preserving brand identity and consumer trust, yet their misuse through exploitative practices like trademark trafficking threatens the integrity of trademark law. Trademark trafficking refers to the registration of trademarks without any bona fide intent to use them, often for speculative purposes including selling them for profit or blocking competitors. In contrast, trademark licensing is a legitimate mechanism that allows a trademark owner to permit another entity to use the mark under agreed terms. The fine line between licensing and trafficking often blurs, creating a legal maze for businesses and authorities.

Trademark Licensing in India- Legal Boundaries and Misuse

Trademark licensing, while a legitimate commercial strategy, is closely linked to the issue of trafficking as it acknowledges the inherent value of trademarks while also raising concerns about their potential commercialization as tradeable assets. Unlike tangible commodities, trademarks are meant to signify a business’s identity rather than serve as independent instruments of commerce.

Under the Trade Marks Act, 1999, India permits the licensing of registered trademarks by authorized third parties including both registered and unregistered entities, provided a written agreement exists with the trademark proprietor. While the Act does not explicitly regulate the licensing of unregistered trademarks, courts have upheld such agreements under common law principles. However, if a license is misused, such as being applied to goods unrelated to those of the proprietor, it may result in the removal of the trademark from the register.

The Supreme Court of India has affirmed that an unregistered license remains valid under common law. In the landmark Gujarat Bottling case, the court ruled that an unregistered licensee could lawfully use a trademark, provided three essential conditions were met:

- it does not mislead the public or create confusion,

- it does not dilute the distinctiveness of the mark, and

- it maintains an identifiable link between the trademark owner and the goods being sold.

Furthermore, the Act places specific obligations on registered licensees. Section 50 empowers the Registrar to modify or cancel a registered user’s entry under certain conditions, though this applies only to registered licensees. Additionally, Sections 57 and 58 allow for the removal of a trademark from the register if licensing conditions are violated.

The evolution of trademark licensing law demonstrates an effort to regulate licensing while ensuring that trademarks retain their fundamental purpose i.e., serving as indicators of origin rather than mere commodities. While licensing acknowledges the intrinsic value of trademarks, it cannot be misused to treat them as standalone tradeable assets. If a trademark license is granted solely for commercial gain without being tied to actual goods or services, it then constitutes trademark trafficking.

Addressing Trademark Trafficking: A Flawed Legal Approach

Courts have time and again held that trademarks are not independent marketable assets and derive their value solely from their association with a business and its offerings. The concept of trademark trafficking was first highlighted in Re Batt (J.) & Co., where the court described it as a form of stockpiling trademarks solely for commercial bargaining rather than for legitimate business use. Similarly, the Supreme Court of India has addressed the issue by clarifying that obtaining a trademark registration without any intention to use it, solely for resale or profit, constitutes trafficking. While the Trade Marks Act, 1999 does not explicitly define “trafficking,” Indian jurisprudence has widely accepted this principle to prevent the misuse of trademark law.

The legal framework for tackling improper trademark licensing and trafficking presents several challenges. Courts have typically responded by invalidating trademarks and removing them from the register, effectively stripping them of protection. However, this approach raises a significant concern since once a trademark is expunged, infringement actions can no longer be pursued, potentially leading to widespread unauthorized use. If consumers remain unaware of the trademark’s de-recognition, they may continue associating it with its previous quality, increasing the risk of deception until they eventually realize that the mark no longer holds legal standing.

Some argue that a trademark should only be removed when consumer deception is already occurring, implying that the level of confusion would not increase post-removal. However, this assumption is problematic. Allowing multiple entities to use an unprotected mark even for a short period, can cause greater harm than a single unscrupulous trader exploiting it.

An alternative approach suggests that instead of invalidating the trademark, only the rights of the licensee involved in trafficking should be revoked. However, in India, there is a distinction between registered and unregistered licensees, making this solution ineffective. While cancelling the registration of a registered licensee is a viable remedy, it does not address issues arising from unregistered licensees. In such cases, courts often resort to cancelling the trademark itself.

Towards Effective Solutions

The current legal framework primarily addresses trademark trafficking or inadequate quality control by cancelling the trademark and removing it from the registry. In cases involving unregistered license agreements, the option of revoking the registered licensee’s rights is not available, often leaving courts with no choice but to invalidate the trademark. However, this approach is flawed, as once a trademark is de-recognized, it becomes open to unrestricted use, exposing consumers to widespread passing off. Additionally, the original proprietor suffers significant losses, as they are stripped of both their trademark and the rights attached to it.

Several measures can be implemented to address these challenges. One potential solution is to mandate a public announcement before cancelling a trademark, ensuring that consumers are informed about its impending de-recognition. However, the effectiveness of this approach remains uncertain, particularly for trademarks with widespread geographical recognition, where public awareness may still be limited.

Another possible legal reform is eliminating the concept of unregistered trademark licensees. If all trademark licensees were required to be registered, courts could directly revoke the license without affecting the validity of the trademark itself.

Conclusion

In addressing the complexities of trademark licensing and trafficking, it is crucial to uphold the integrity of trademark law while ensuring fair commercial practices. The existing legal framework, though effective in addressing misuse, often falls short in protecting both consumers and rightful proprietors. Reforming the law to enhance public awareness of trademark cancellations and mandating the registration of licensees could offer more balanced solutions since ultimately, the goal should be to prevent exploitation while preserving the true function of trademarks that serve as reliable indicators of origin and quality in the marketplace.