Decoding IPR

Trademark Bullying: The Unregulated Weapon in Corporate Warfare

Introduction- Unpacking Trademark Bullying

Introduction- Unpacking Trademark Bullying

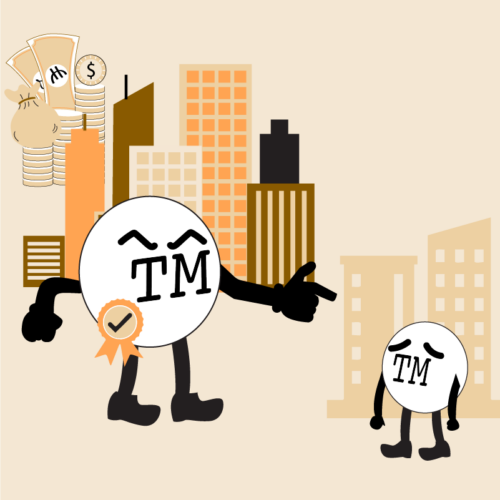

In the modern marketplace, where brand identity often determines business success, trademarks have become potent corporate assets. But what happens when these tools of protection morph into instruments of suppression? The phenomenon of trademark bullying, where dominant brands use their financial and legal muscle to unfairly target smaller competitors under the guise of protecting intellectual property, is becoming a growing concern. Although legal systems across jurisdictions recognize the importance of preventing consumer confusion, the aggressive and often baseless enforcement of trademark rights threatens to undermine healthy competition and innovation.

A recent case from the United States provides a classic example. The popular chili oil brand Momofuku issued a cease-and-desist letter to a much smaller brand, Homiah, alleging potential consumer confusion between their respective products: Momofuku Chili Crunch and Homiah Sambal Chili Crunch. Visually, the two couldn’t be more distinct since Momofuku’s minimalist jar contrasts sharply with Homiah’s colorful floral packaging. Despite this, the larger company pursued legal threats, possibly betting on the financial pressure to make the smaller business cave. Big brands are generally insecure about the similar products in the market and using their dominant position, they tend to wipe out the smaller companies alleging trademark infringement.

Indian Context: A Familiar Battlefield

India is no stranger to such tactics. Over the years, established brands have routinely employed their dominance to stifle budding competitors through aggressive trademark enforcement. A prime example is the Subway IP LLC v. Infinity Foods & ors, case, where despite the defendant making significant changes to their branding and logo, the global sandwich chain Subway continued to litigate. Ultimately, the Delhi High Court found Subway’s claims to be unjustified, stating that there was no likelihood of confusion among consumers. Yet, the court imposed no penalties on Subway for initiating what could be seen as vexatious litigation, highlighting a gap in the system that allows larger entities to intimidate smaller businesses without consequence.

Similarly, BigBasket issued a cease-and-desist letter to a small Coimbatore-based grocery startup, DailyBasket, objecting to the use of the common term “Basket” in its name. The startup publicly countered the notice, arguing that “basket” was generic and widely used in the industry. This move by BigBasket was seen by many as an attempt to throttle a potential competitor under the guise of protecting its trademark, despite no real risk of consumer confusion.

Another instance is the Marico vs. Baidyanath dispute, where Marico, the owner of the “Saffola” brand, claimed infringement over Baidyanath’s use of the mark “Saffo-Life.” Though the court ultimately favoured Marico, the case raised concerns over whether dominant players in the market are leveraging trademark law to monopolize common prefixes or product associations.

All these cases reflect a broader pattern in India: the increasing use of trademark law not just to protect identity, but to suppress competition. While such actions may fall within the bounds of legality, they blur the ethical lines between rightful enforcement and predatory litigation. In the absence of explicit statutory provisions or punitive costs for frivolous claims, the Indian legal landscape continues to offer fertile ground for trademark bullying.

The Legal Lacuna: Section 142 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999

Section 142 of the Indian Trade Marks Act was introduced to provide some relief to individuals or businesses who are threatened with unjustified claims of trademark infringement or passing off. If someone receives such threats, they can approach the court for a declaration that the threats are baseless, seek an injunction to stop further harassment, and even claim damages.

However, while this provision seems promising on paper, it has several practical shortcomings. For one, the law doesn’t clearly define what qualifies as an “unjustified threat.” Courts often use terms like “groundless threats” or “unwarranted legal notices,” but the interpretation remains murky. This vagueness is a loophole that large corporations often exploit. Armed with vast legal and financial resources, they can send intimidating legal notices to smaller players even if their claims are flimsy, just to scare them into backing down.

Moreover, Section 142 lacks any real teeth. Although it allows victims to claim damages, Indian courts rarely impose penalties or costs on the parties making these threats. This means that even if a big company repeatedly sends baseless legal threats, it suffers little to no consequences. The law is also reactive, it only helps after a threat has been made. The smaller party, already burdened by fear of litigation, must then spend time and money pursuing relief through the courts, which many startups and small businesses simply cannot afford.

Worse still, the protection under this section becomes almost useless once the trademark holder files an actual lawsuit. Sub-section (2) makes it clear that once legal proceedings are initiated, the provision no longer applies. Courts have consistently upheld this interpretation, ruling that while baseless threats can be restrained, the right to initiate legal action cannot be curtailed. As a result, large companies often bypass this protection by quickly filing a case, even a weak one, just to neutralize any pushback from the smaller party.

Even in instances where courts have found that the infringement claims were clearly unjustified or even malicious, they have hesitated to impose heavy costs on the aggressor. This lack of deterrence emboldens powerful businesses to weaponize trademark law, burdening startups and small entrepreneurs with expensive and exhausting legal battles. Until Section 142 is strengthened both in its wording and in its enforcement, it remains a weak shield in the fight against trademark bullying.

Tackling Trademark Bullying- The Way Forward

To effectively tackle trademark bullying, India needs a multi-pronged approach:

- Involving the Trade Marks Registry: Drawing inspiration from the U.S. model, India could enhance the role of the Trade Marks Registry by empowering it to act as an initial gatekeeper. Trademark owners who wish to send cease-and-desist notices would first need to submit a prima facie claim to the Registry. If the Registry deems the claim to be weak or without merit, it could issue a warning or refuse to validate the notice. This early intervention would provide smaller businesses with a protective barrier against unwarranted legal threats, reducing the chances of them being forced into costly and time-consuming litigation.

- Judicial Overhaul: The Indian judiciary needs to take a more proactive stance in cases involving trademark disputes. Courts should look beyond mere legal technicalities and consider the broader context, such as the market dominance of the plaintiff, the actual impact on competition, and the real risk of consumer confusion. Establishing clearer, more transparent guidelines that differentiate legitimate trademark enforcement from bullying is vital. Furthermore, the judiciary should not hesitate to impose substantial damages or costs on large corporations that pursue frivolous claims, thereby acting as a deterrent to those attempting to misuse their trademark rights.

- Codification and Definition: The absence of a formal definition of trademark bullying in Indian law hampers its redressal. The legislature should incorporate a definition and provide penal provisions for malicious or frivolous enforcement. Codifying such safeguards would not only act as a deterrent but also empower courts and regulators to address the issue with more precision.

- Support Mechanisms for SMEs: Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often find themselves at a disadvantage when faced with the financial and legal power of larger corporations. To level the playing field, the government should establish dedicated support systems, such as legal aid cells or panels, which offer guidance and mediation services to SMEs involved in trademark disputes. These support mechanisms would help alleviate the financial burden on smaller businesses, enabling them to defend themselves without the fear of being crushed by costly legal proceedings.

Conclusion

Trademark rights are essential to protecting brand identity and consumer trust. But when these rights are enforced disproportionately, they become tools of oppression. Trademark bullying represents a dark side of IP enforcement- one that fosters monopolies and kills competition in its infancy.

India stands at a critical juncture. As its startup ecosystem booms and more small businesses enter competitive markets, a fair trademark regime is not just a legal necessity but an economic imperative. By recognizing, codifying and curbing trademark bullying through judicial, legislative and administrative reforms, India can ensure that its trademark law remains a shield and not a sword, in the hands of corporate giants.